Cinematic enfant terrible Gaspar Noé has been shocking audiences with his artistic films of graphic violence for over 20 years. In IMDb he is quoted as saying:

"There is no line between art and pornography. You can make art of anything. You can make an experimental movie with that candle or with this tape recorder. You can make a piece of art with a cat drinking milk. You can make a piece of art with people having sex. There is no line. Anything that is shot or reproduced in an unusual way is considered artistic or experimental."I haven't seen a Noé film myself, so I can't offer any personal opinions. The descriptions themselves are so graphic and repellent that I've avoided them.

What can Noé and neuroscience possibly have in common? Neurologist/cognitive neuroscientist Dr. Guillén Fernández and colleagues have been showing clips from Irréversible to participants in fMRI studies.

The film employs a non-linear narrative and follows two men as they try to avenge a brutally raped girlfriend. ... Several reviewers declared it one of the most disturbing and controversial films of 2002.1Why would researchers show this film to [perhaps unsuspecting]2 college students? To quickly induce a state of extreme psychological stress. In brief, Fernandez et al. are interested in studying the brain under acute stress. A PubMed search suggests there are at least 16 articles using this methodology.

One such study examined rapid changes in neural network connectivity induced by the Irréversible stress-induction procedure3 (Hermans et al., 2011):

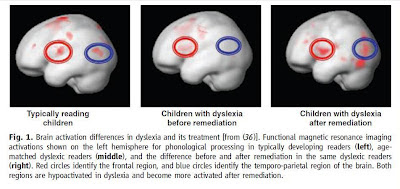

During exposure to a fear-related acute stressor, responsiveness and interconnectivity within a network including cortical (frontoinsular, dorsal anterior cingulate, inferotemporal, and temporoparietal) and subcortical (amygdala, thalamus, hypothalamus, and midbrain) regions increased as a function of stress response magnitudes.The data analysis strategy employed the methods of "neurocinematics" (Hasson et al., 2008) to find inter-subject correlations (ISCs) in the BOLD response during free viewing of the film clips. Then the regions that responded to the aversive film to a greater extent were identified. These included areas associated with interoception and autonomic-neuroendocrine control, peripheral stress effector systems and catecholaminergic signaling, and sensory and attentional (re)orienting.

Fig. 1 (Hermans et al., 2011). ISCs. Maps are thresholded at P < 0.05, whole-brain FWEcorrected, and overlaid onto cortical surface renderings (A and B) and a canonical structural MRI (C). FI, frontoinsular cortex; SMA; supplementary motor area; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex; (v)mPFC, (ventro)mPFC; IFG, inferior frontal gyrus; Th, thalamus; Mb, midbrain; Hy, hypothalamus.

Then "multisession tensorial probabilistic independent component analysis" was used to test for functional connectivity between these regions, which overlapped with the "salience network" observed in resting state studies (Seely et al., 2007). Finally, pharmacological manipulations suggested that the stress-induced connectivity within this network was decreased by blocking β-adrenergic receptors [via propranolol], but not cortisol synthesis [via metyrapone].

If you happen to be in Chicago for the 2012 CNS Meeting, you can learn more from Dr. Fernandez himself, who will be speaking in Symposium Session 1:Talk 4: Equipped to Survive: Large-Scale Functional Reorganization in Response to Threat Enables Optimal Behavior

Unfortunately, this presentation conflicts with Joshua Carp's talk, mentioned in the previous post -- How vulnerable is the field of cognitive neuroscience to bias?

Footnotes

1 Watch the trailer for Irreversible [NOTE: .

2 Participants with "regular exposure to extremely violent movies or computer games" are excluded from the studies.

3 The presented film clips were described as follows:

Fragments (both 140 s) from two different movies entitled "Irréversible" (2002), by Gaspar Noé, and "Comment j’ai tué mon père" (2001), by Anne Fontaine, were selected to serve as aversive and neutral control movie clips, respectively. ... Matching for audiovisual characteristics (see table S1) was performed by the authors by selecting aversive and neutral clips out of a set of candidate clips which best matched on the following measures: presence of faces in the foreground, presence of background actors, amount of distinct camera movements, and percentage of time the camera was moving. Selected aversive scenes contained extreme male-to-male aggressive behavior and violence in front of a crowd. Neutral control scenes also contained people interacting in the foreground in the presence of a background crowd. Fragments were equalized in luminance. Both movies are French spoken, but selected movie clips contained minimal speech.

References

Hasson U, Landesman O, Knappmeyer B, Vallines I, Rubin N, Heeger DJ. (2008). Neurocinematics: The Neuroscience of Film. Projections 2:1-26. [PDF]

Hermans, E., van Marle, H., Ossewaarde, L., Henckens, M., Qin, S., van Kesteren, M., Schoots, V., Cousijn, H., Rijpkema, M., Oostenveld, R., & Fernandez, G. (2011). Stress-Related Noradrenergic Activity Prompts Large-Scale Neural Network Reconfiguration. Science, 334 (6059), 1151-1153 DOI: 10.1126/science.1209603

Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, Keller J, Glover GH, Kenna H, Reiss AL, Greicius MD. (2007). Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J Neurosci. 27:2349-56.

Further Reading:

Neurocinema, Neurocinematics

The Hyperscanning of 'Paranormal Activity': A Neurocinematic Study of Collective Fear